“Twenty years ago, 50 years ago, athletes got full scholarships. Television income was what, maybe $50,000? Now everybody’s getting $14, $15 million bucks and they’re still getting a scholarship.”

-Steve Spurrier

Introduction

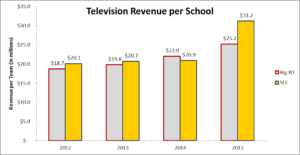

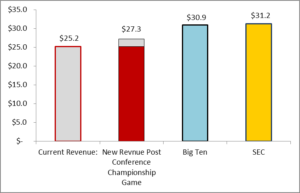

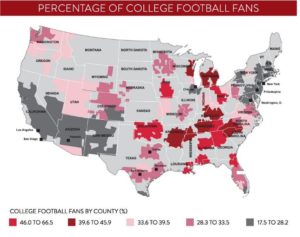

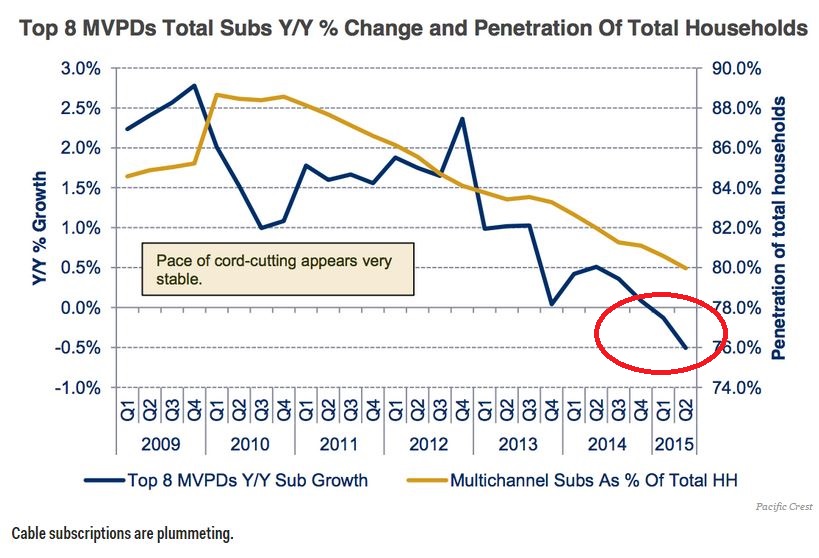

In 1949 the NCAA enacted the “Sanity Code” which prevented college athletes from receiving any direct or indirect benefits as compensation. At the time the rule made sense, but as Steve Spurrier mentions above NCAA Division 1A Football (or Football Bowl Subdivision “FBS”) was not the big business in 1949 as it is today and the time has come to revise the rules to reflect the change in times. Today the NCAA Football economy draws over $3 billion in revenue on a yearly basis, with many of its bigger programs earning over $50 million in profits; yet its players are compensated no differently than in 1949. The players who are responsible for generating such revenues are only compensated by receiving free tuition (non-guaranteed past one year) and a small monthly housing allowance. To make matters worse, student athletes are only guaranteed one year of free tuition when they sign a letter of intent, yet coaches can prevent an athlete from transferring to another institution to play football; the system takes advantage of the very people it claims to protect.

According to a report by the National College Players Association, “an advocacy group for college athletes found that the average full scholarship at a Football Bowl Series university lacks $3,222 in educational expenses, including everything from parking fees to utilities charges. Just paying players this much, the report says, could “reduce their vulnerability to breaking NCAA rules.”2 Coaches receive multi-million dollar contracts yet the people most responsible for the product on the field are left frustratingly uncompensated. In the words of 1991 Heisman Trophy Winner Desmond Howard, “You see everybody getting richer and richer, and you walk around and you can’t put gas in your car? You can’t even fly home to see your parents?”

These institutions and conferences are not the only ones getting richer; the NCAA and the

corporations involved make a great deal of money as well. What is most flabbergasting about this situation is that the NCAA claims that they are “protecting student athletes” by forcing them to maintain their amateurism. In order to be eligible to compete in the NCAA, every student athlete must sign a “Student Athlete Statement” which ensures their status as amateurs by waiving their right to benefit financially from their athletic performance. While the players “waive” their right to earn money from their accomplishments, the NCAA and member institutions continue to make money off of the players on and off the field, using players’ likeness for advertising and other purposes. Even more appalling is that many athletic departments do not allow their athletes to take classes that could get in the way of their athletics. This leaves athletes unchallenged in the classroom and unable to capitalize on the free education which they are receiving. It is laughable to believe that

any of this “protects” the student athlete? Last year the NFL paid their players over $35 million for using players’ likeness in an Electronic Arts video game while the NCAA did not compensate a single athlete for a similar game. How does a student athlete benefit when their likeness is used and they do not receive any compensation? The fact is that these 18-21 year-olds serve as free labor for a multi-billion dollar industry where powerful institutions take advantage of the young and less educated, and it is time for the NCAA to remedy its past discretions.

In order for the NCAA to rid itself of the corruption that exists and create a fair system where everyone prospers, it is necessary to pay the players and grant them the rights that they have not had to this point which will allow them to have a better chance for success in the future, both on and off of the field. We propose a plan that will force teams to pay their players and also implement a salary cap system. Creating a salary cap system will not only fairly compensate the athletes it will help enable parity in the recruiting process across all FBS programs. The plan also will ensure that every FBS college football player is guaranteed five years of education and that players are be covered medically for life for any injuries sustained while on the field of play.

Plan

The basis of the plan will be two sided. One side will discuss the salary cap system and the other will focus on the education and health guarantees in which the student-athletes are entitled to receive.

Risks

Before getting into the details of the 5-5 Plan, it is important to recognize that there are a number of risks in the NCAA allowing athletes to receive a salary. The United States judiciary system would become involved in labor issues and it is possible that the NCAA would face heavy legal battles once they have recognized the athletes as employees. Athletes could attempt to unionize and make certain demands which could jeopardize the goals of the 5-5 Plan. Despite the risks, we believe that this is the most appropriate way to compensate the athletes without compromising the integrity of College Football. These student athletes are unpaid labor and we believe that the NCAA needs to make drastic changes in order to live up to their commitment of doing what is best for the student athlete.

Five Years

Since 1973 the NCAA has prohibited member institutions from guaranteeing athletic scholarships for more than one year; as a result players are vulnerable each year to not having their scholarship renewed. Analysis of top Division I basketball teams show that 22% of scholarships were not renewed from 2008 – 2009. This decision falls on the shoulders of the coach, and in cases where players do not perform up to expectations; players will be released from their scholarship and be forced to pay for school if they want to remain enrolled. Considering the amount of money that these institutions make off of these players, we feel that it is irresponsible for the coaches to have the authority to discontinue a student-athlete’s education, unless the reason has to do with a clear

cut disciplinary action. The one-year rule effectively allows colleges to cut under-performing student athletes just as pro sports teams cut their players which is counter to the NCAA’s claim that its highest priority is protecting education.

We propose that each player be guaranteed five free years of education in exchange for signing a letter of intent. Unless the player is removed for disciplinary purposes or volunteers to quit the team, the player will receive the five year scholarship regardless of on field performance. We believe five years make more sense than four because of the rigorous schedule that football players undertake.

Recently there have been cases reported at UNC where players have been forced to enroll in easier courses because anything more difficult would conflict with their commitment to the football program.3 This situation is not unique to just UNC as players across the country deal with these same restrictions from their athletic department. Only 2% of NCAA Football players are drafted by NFL teams and these Universities need to give each player the opportunity to be in the best possible situation for the future. Not all players will take advantage of a fifth year, however given the demands on these players it is essential that these players have five years to complete their studies to prepare themselves for life after football.

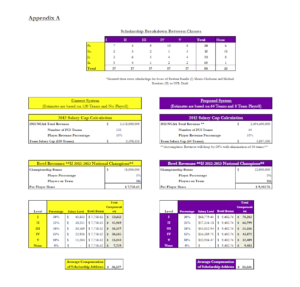

Five Tiers

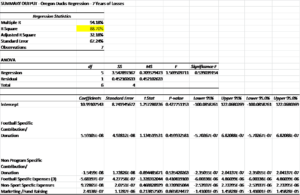

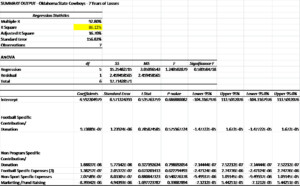

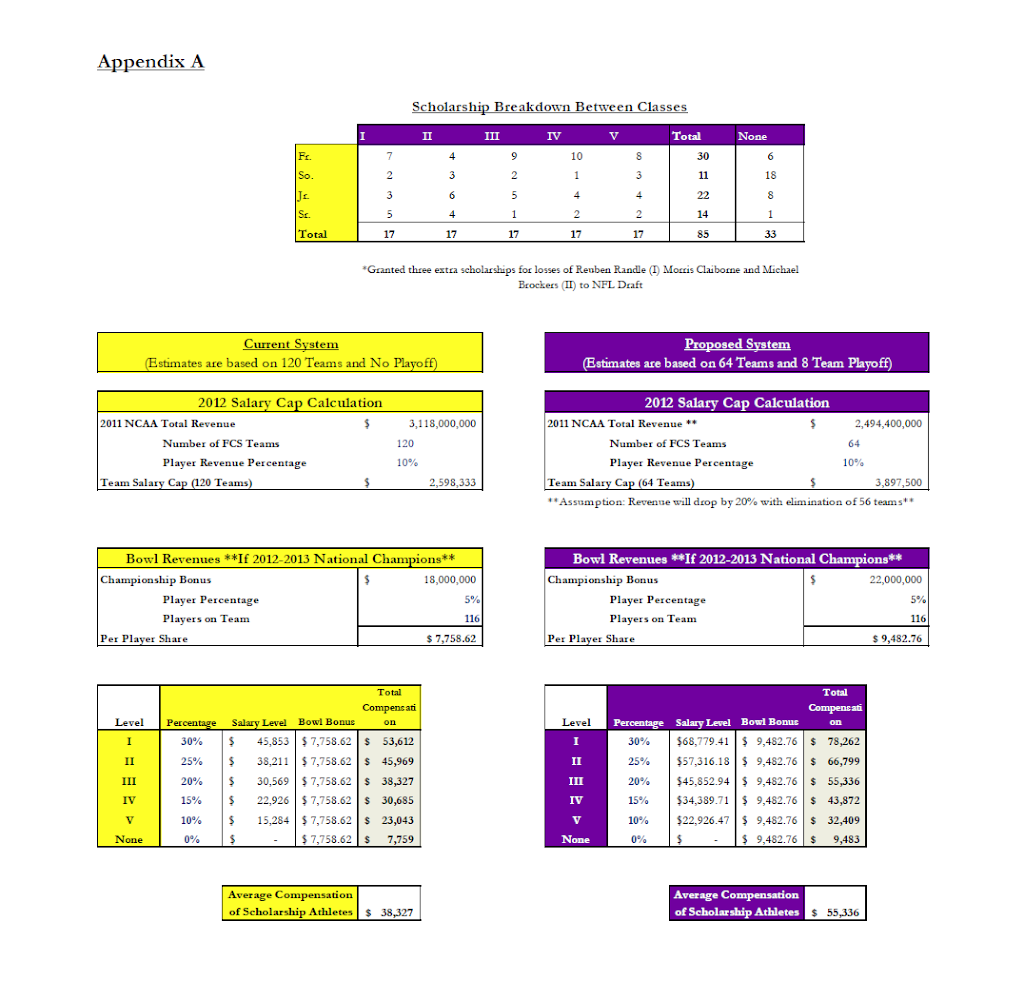

The NCAA would adopt a five-tier salary cap system which would be based on revenues from the previous season. For professional sports in North America the players receive on average about 50% of league revenues from TV contracts and ticket sales. Taking into account that the players are still in college, the student athletes will share 10% of all pre-bowl revenues. Each FBS school will have the same salary cap in which to pay the players, the sum of which across all schools will make up the 10% of league wide revenues. Tuition costs will not count against the 10% of revenues.

Under the new system, each team will be allowed to issue 85 scholarships, the 85 will be broken into five levels of scholarship; seventeen players will be allocated to each tier. Every player would be guaranteed five years of scholarship in addition to their salary. Players will earn a salary as long as they are on the team’s roster and still carry eligibility to compete. If a player has exhausted his eligibility after four year, he will still have a year of scholarship remaining however he will not receive a salary since he is ineligible to play football. The player’s salary is not guaranteed each year, however if a player from the “I Tier” is dismissed from the team, the team cannot re-allocate that tier to another player unless unique circumstances exist. The only way for a team to re-use one of the spots is if a player either transfers or turns professional. If a player transfers between institutions

they are not permitted to join another school at a higher salary level.

I Tier – 30% of salary cap (17 players)

II Tier – 25% of salary cap (17 players)

III Tier – 20% of salary cap (17 players)

IV Tier – 15% of salary cap (17 players)

V Tier – 10% of salary cap (17 players)

Tier Mobility

Any player has the ability to be moved up to a higher tier of salary; however no player can be unwillingly demoted to a lower tier. Coaches may dismiss a player from the team and end his salary; however that tier scholarship cannot be re-used on another player, existing or incoming unless special circumstances apply and it is approved by the NCAA. This will prevent coaches from shuffling players between levels and trying to manipulate the system. If a player chooses to transfer to another FBS school, they will still have to sit for a year and will not be able to join their new team at a higher tier than they had been previously. This will prevent coaches from having the ability to lure players at lower tier levels by offering them a better compensation package. If a player declares for the NFL Draft their scholarship will be vacated and eligible to use on another player. A walk-on

can be rewarded with a scholarship within a team at any tier, however if the walk-on chooses to transfer they may only enter at a “V Tier” scholarship.

Bowl Bonus

At the end of each year the players will share 5% of revenues from their University’s Bowl winnings. Unlike the salary cap system where each tier of players receives a different salary, each player on the roster will receive the same portion of the revenue, including non-scholarship players. The Bowl Bonus serves as a reward for the teams that perform better over the course of the year and incentivizes players to perform at the highest level regardless of which bowl their team participates.

Partial Lifetime Benefits

One of the most important tenants of this plan will be the partial lifetime benefits for which players will be eligible. This is clearly be a sticking point with many of the Universities; however we feel strongly that if a player is injured during his college football career the onus should fall on the University to make sure that player is covered financially for any future bills they might incur. The plan would leave each FBS team responsible for the insurance of each of their players and responsible for any long term injuries sustained on the field of play during their college career. When an injury occurs, team doctors will document the injury, the rehab as well as the long term prognosis. If it is proven that a player is suffering after the end of their career because of injuries sustained on the field during college practice or play, the responsible University and their insurance company will be responsible for paying the athlete’s benefits. Under the 5-5 plan, players will have

lifetime coverage for these injuries. It is unfortunate enough that players are not currently paid in the FBS, but it is simply tragic that players who experience devastating injuries do not receive continued medical coverage from the institutions that make millions off of them.

Endorsement Opportunities

Under the new system players will not be able to receive individual endorsements and will not be compensated by the university for apparel endorsements. The reasoning behind this is that allowing players to be compensated in an unregulated fashion would detract from the salary cap system because boosters would be able to influence the system. The point of the salary cap is to keep all universities on an even playing field, if players are allowed to receive unregulated money than the scholarship tiers become useless because players would flock to the schools which have the most money.

Preventing Cheating

One of the goals in paying players is that it would prevent the cheating which occurs today; in order to accomplish this goal the NCAA would have to increase severity of the penalties on cheating institutions. In 1986, Southern Methodist University was handed down the “Death Penalty” after proof surfaced that players had been paid by boosters; it was the harshest penalty in NCAA Football history. However since the SMU incident, infractions have continued yet punishments have become less severe. Over twenty NCAA Football programs have been eligible for the “Death Penalty” since 1986, but none have received it and most believe no program ever will again. A study by CBS Sports4 revealed that over the past 25 years the majority of NCAA teams that have been penalized have had a higher winning percentage in the five years after receiving punishment than in the five years before receiving the punishment. For the NCAA, an organization which prides themselves on fairness and preventing competitive advantages through the recruiting process, this is unacceptable. A team which continually breaks NCAA rules should receive harsh punishments and only on the rare occasion be able to return to a high level of competition in the years after the infraction was committed. The problem is that with all of the money on the line with TV deals and advertisements the NCAA would rather give a program a minor infraction than to cripple the program with a “Death Penalty.”

The way to solve this problem is to become far stricter on rule enforcement and notify teams that any infractions will not only result in harsh penalty, but players (the ones found innocent) will be allowed to transfer to another institution without sitting out or forfeiting a year of eligibility. The return of the “Death Penalty” with a transfer provision would change the way that teams operate and deter them from cheating in the future. If teams believe that they will lose future seasons and the current players will be allowed to jump ship without penalty more will do their best to run a clean program.

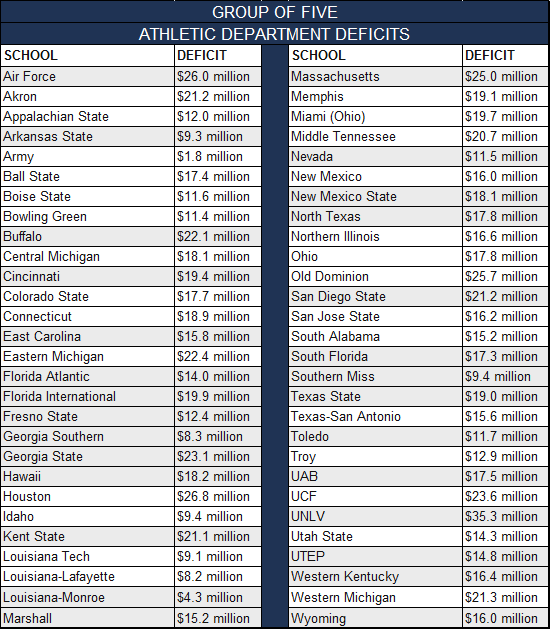

Downsizing of Division 1-A

One of the most significant effects that a salary cap would have is the elimination of noncompetitive teams in Division 1-A. There are currently 120 FBS schools in the NCAA, each of these teams is eligible (in theory) to win the National Championship. The problem is that there is such a disparity in talent and money between the top 40 and the bottom 40 teams that rarely do the bottom 40 teams ever have a chance at post season play. There is very little mobility from the bottom part of the FBS because financially these teams are unable to compete with bigger schools and bigger budgets. For example, the bottom 40 schools in the FBS in 2010 averaged roughly a paltry 18,000 fans per game. Contrast this to the top 40 which averaged roughly 80,000 fans per game and the middle 40 which averaged a respectable 45,000 fans per game. Lower attendance in addition to the

smaller TV contracts which the lesser teams receive would force many of these bottom teams to move from the FBS to the FCS in order to remain affordable for their University. Downsizing the FBS to 64 schools would allow teams to drop the bottom-feeders and allow the better teams to play a more competitive schedule.

Creation of Parity = Increase in Quality

Creation of a tiered salary cap system would create recruiting parity across Division 1-A football schools. With players only permitted to receive compensation through their tier of scholarship, the salary cap system would force each team to spend the same amount of money on the players, which in turn would create a level playing field for recruiting. A level playing field for recruiting would prevent the typical top schools from attracting all of the top talent because it would be financially beneficial for a player to go to a lesser program if they received a higher level of scholarship at that institution. In 2012 each of the top five schools had 15+ recruits that graded out at four-stars or better, including 15 of the 33 five-star players. Of the teams outside the top 20, none had more than 1 five-star recruit and all but five schools had less than 5 players ranked as four-star players. These rankings are not always indicative of the success that these players will achieve as college players, however with such inequality in the recruiting process it is no surprise that the same teams battle for the National Championship every year.

One side-affect to greater recruiting parity would be an increase in quality and player development in college football. One of the disadvantages for players with the current recruiting process is that when the best players go to the same schools, some great players have to sit on the bench because they are playing behind a better player. There are many cases where these players do not develop properly due to a lack of playing time and miss the opportunity to continue their football careers. If these players instead went to places where they would play right away, more of the top prospects would have the opportunity to receive playing time and develop rather than to sit on the bench and

wait for a star player in front of you to graduate. If the best players were spread across all FBS teams not only would the quality of play improve but with higher quality opponents on a weekly basis more players would likely reach their potential.

The above paper was written in May of 2012 by my friend and colleague, Christopher Brooks, during our final year at the Darden School of Business in conjunction with my paper on the BCS.

1.“BCS Must Change and TV Will Lead the Way” Nwokedi, Brian

2. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904060604576572752351110850.html

3. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/10/opinion/nocera-football-and-swahili.html

4. http://www.cbssports.com/collegefootball/story/15312728/major-ncaa-violations-yield-relatively-minorconsequences